Five ‘truths’ about investing – and why they are hogwash

Archived article

Archived article: please remember tax and investment rules and circumstances can change over time. This article reflects our views at the time of publication.

If, like me, you are interested in investing and read avidly about it, you might have noticed the internet is awash with touted investment principles. Many sound sensible and have been repeated so many times they’ve come to be commonly accepted as “investment truths”.

But are they? Some are complete nonsense in my view. They are also dangerous, because they can encourage the wrong actions and behaviours.

Thankfully, simply being aware of them could go a long way to reducing their impact.

Important: This article outlines Charlie’s personal investment views. It is not a personal recommendation to buy, sell or hold any of the investments mentioned. Experienced investors should form their own considered view or seek advice if unsure. Charlie personally holds shares in Diageo. This article is original Wealth Club content.

‘Truth’ #1: Great

investing means performing well all or most of the time

Every investor must be willing to look foolish in the short term, if they want superior long-term returns.

Take Warren Buffett, arguably the greatest investor of all time.

In 1999, the US stock market rose 21%. Buffett’s investment vehicle, Berkshire Hathaway, lost 19.9%. This is because he avoided technology shares. But look what happened when the tech bubble burst – he handsomely outperformed.

Berkshire Hathaway vs. US stock market in tech boom/bust (% change)

This has been the story of Buffett’s career. He’s never been afraid to look like an idiot, to be proven right eventually. In 1999, Buffett was labelled a dinosaur, and even in recent years as loss-making tech companies soared, many claimed he’d lost his touch. But his long-term track record speaks for itself.

Many professional investors don’t think like Buffett. They can’t bear the thought of underperforming, even for a few quarters. They would rather aim for mediocrity than risk getting fired for departing from the crowd. This leads many fund managers to run excessively diverse portfolios that look quite a lot like the index, or to try and change styles to suit prevailing conditions. This invariably ends up damaging long-term returns.

I’m firmly on the side of Buffett. I don’t expect to perform well all the time. My aim is to perform well over time. This means accepting periods of underperformance and keeping my eyes glued to long-term business prospects, not share prices. Most of all, it means having the courage, discipline and patience to stick to my investment process, especially when it falls out of favour.

‘Truth’ #2: The more information you have, the better

I seek to thoroughly understand the companies I’m investing in. But beyond a certain point, accumulating more information is counterproductive, in my experience. It leads to a false sense of confidence – and distracts from the few business factors that really count.

For most businesses, only a few things genuinely matter. I focus on understanding those as well as I can, and try to ignore everything else.

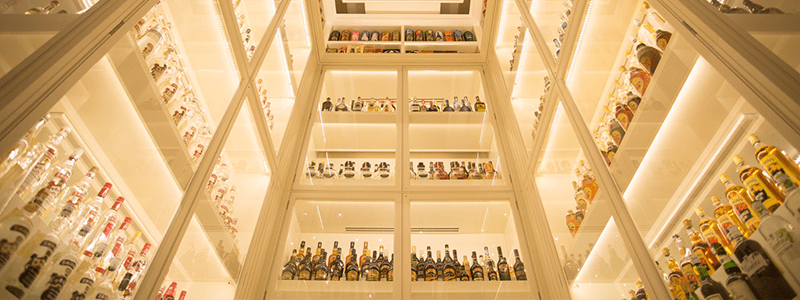

Take Diageo, the alcoholic beverage manufacturer. I think two things really matter for this company. Firstly, more people are drinking premium spirits, driving demand for Diageo’s products. Secondly, Diageo has a diverse portfolio, underpinned by numerous competitive advantages (such as strong brands and formidable distribution networks) to capitalise on the opportunity.

Take Diageo, the alcoholic beverage manufacturer. I think two things really matter for this company. Firstly, more people are drinking premium spirits, driving demand for Diageo’s products. Secondly, Diageo has a diverse portfolio, underpinned by numerous competitive advantages (such as strong brands and formidable distribution networks) to capitalise on the opportunity.

Everything else, including how the economy is performing this year or what interest rates are doing, is largely noise. That’s not to say these factors won’t impact the share price in the short term – they probably will. But those first two factors will determine the long-term outcome for Diageo’s shareholders.

I’m also not convinced it’s possible to have more or better information than anyone else in this day and age. Lots of information is freely available on the internet, and listed companies are required to quickly disclose anything they think could move the share price.

‘Truth’ #3: Facts, formulas and figures matter more than what can’t be measured

There is an obsession with spreadsheets in the investment industry. But data tells you more about what a company has done, rather than what it will do. It also tends to have a short shelf-life.

A great example is this year’s earnings per share. Every man and his dog are trying to forecast this number, and the factors that influence it. But the value of a business depends on the cash it produces over its whole lifetime, not what it makes in any given year. This year’s profit can be influenced by all sorts of factors that might not matter a few years from now – such as whether people are allowed out of their homes, because there’s a pandemic.

I pay much more attention to intangible factors – like culture, moats, competition and how a company’s product or service is perceived – than I do to facts and formulas. These factors are more difficult to measure, and impossible to boil down to a number in a spreadsheet. But to my mind, they will have the biggest influence on business performance over a decade.

This quote from Nick Sleep, who managed the Nomad Investment Partnership, sums it up:

“Investors tend to latch on to what can be measured, aided by the accountants and to some extent by their own laziness. But there is a wealth of information in items expensed by accountants, such as advertising, marketing and research and development, or in items auditors ignore entirely such as product integrity, product life cycles, market share and management character.”

In other words, you’re better off focusing on management character than this year’s financial statements. Few investors seem to understand this, and I think even fewer apply it.

‘Truth’ #4: Rising stock markets are a cause for celebration

I generally prefer it when stock markets fall, because lower prices today mean a greater chance of higher returns in the future.

The lower share prices are, the more share buybacks and reinvested dividends are worth. Both are major drivers of long-term returns. Business acquisitions are also likely to be cheaper in a market downturn, providing more opportunity for shrewd acquirers.

More importantly, the best companies usually get stronger during a downturn. This is because weaker competitors tend to fall by the wayside (they either go out of business or significantly retrench). Strong businesses with the margins, cash flows and balance sheets to maintain investments can often gain market share in such conditions.

Consider the banking sector during the 2008/09 financial crisis.

In the aftermath, most banks were on the operating table, because they had lent recklessly in the years preceding it. But not all.

For specialist lender Close Brothers, the financial crisis was a huge blessing. The group had prepared well for the crisis. It lent conservatively in the years leading up to it, and its balance sheet was rock solid. When the crisis struck, and most competitors retrenched, Close Brothers pushed down on the accelerator, lending more to new and existing customers, at rich margins. This allowed it to grow profits strongly, coming out of the financial crisis – putting the group in a stronger position than pre-crisis.

Close Brothers’ Banking division profits (£ million)

‘Truth’ #5: The more stocks in a portfolio, the less risky it is

Most funds own upwards of 50 positions; some over a hundred. This makes little sense to me. 15-20 companies, each with different business drivers, should provide ample diversification. The only thing you achieve by going beyond that is diluting your best ideas and attention, in my view.

There are three main reasons I favour a concentrated portfolio:

- Great businesses are rare. Great businesses that are well managed are rarer still. I don’t want to ‘diversify’ my portfolio by adding sub-par companies – because in my view, this increases rather than reduces risk. I agree with investment great, Phil Fisher: it is better to own a few great businesses than a great many mediocre ones.

- Good ideas are rare – at least for me. When I have one, I want it to make a difference.

- I like to understand the businesses I own. There are only so many companies I can track and develop enough knowledge on.

In addition, owning fewer positions forces you to make tough decisions. Do I really understand this business well enough? Would I be better off holding this company instead? To me, this is a better approach than adding more and more names, akin to a stamp collector. There are no prizes in investing for collecting large albums of stocks.

Plus a bonus ‘truth’: The biggest risk is stock market volatility, economics, war, inflation etc.

I’ve included this one as a little bonus, because it draws on lessons from the other five. It’s the very common myth that the biggest risk to investors stems from external events, like the election of Trump or Covid-19.

It’s none of these. The biggest risk to you as an investor is yourself.

It’s trying to get rich quick, rather than being patient and adopting a long-term view. It’s following the herd. It’s lacking the discipline to stick to your process when the tide turns against you. It’s panic selling when the stock market crashes. It’s complacency that follows a period of success.

The good news is that you can control this.

Use patience, discipline, rationality and common sense. Keep things simple. Learn constantly and always remain humble.

See five-year performance of the shares and index mentioned above

Apply online now: Quality Shares Portfolio, managed by Charlie Huggins

The Quality Shares Portfolio, managed by Charlie Huggins and exclusively available through Wealth Club, is a portfolio specifically designed for people who are genuinely interested in investing.

It’s a portfolio of 15-20 global businesses chosen for their resilience, financial strength and pricing power.

It is profoundly different from any other investment you might hold in two key respects. The first is the level of information, insight and transparency it provides (you can see an example here). The second is in the investing approach itself.

You can invest in the Quality Shares Portfolio online, if you’re a high net worth or sophisticated investor. The minimum investment is £10,000; you can invest in an ISA, SIPP or in a General Investment Account, subscribing new money or transferring existing investments.

Liked this article? Register to receive the next one straight into your inbox.

See five-year performance of HL Select UK Growth Shares (Acc)

Wealth Club aims to make it easier for experienced investors to find information on – and apply for – investments. You should base your investment decision on the offer documents and ensure you have read and fully understand them before investing. The information on this webpage is a marketing communication. It is not advice or a personal or research recommendation to buy any of the investments mentioned, nor does it include any opinion as to the present or future value or price of these investments. It does not satisfy legal requirements promoting investment research independence and is thus not subject to prohibitions on dealing ahead of its dissemination.